Colton had just finished his Chiari Decompression. He was headache free and doing great! His neurosurgeon came to me and said, “This is a genetic disorder and Emmalyn should be checked.” Two weeks later I took Emmalyn into the Chicago area to be sedated for her first MRI of the brain and spine. Three hours later I met Emmalyn in recovery where she came out of anesthesia smiling. Emmalyn was three years old and asymptomatic, not even a headache. Colton’s neurosurgeon called me the next day and let me know that she was only 5mm herniated, but in the spinal MRI, she had two separate syrinxes. A smaller one in her cervical spine and a very large one in her thoracic spine. Her opinion was to decompress Emmalyn right away as she was very concerned about the two syringes and explained, “With the decompression, it should allow the syringes to dissipate.” So, we scheduled her first decompression for two-weeks later, on July 31st, 2012. Emmalyn went through her first decompression like a champ and was released from hospital after three days. This is when Emmalyn’s headaches started. It seemed like once a day she would be getting a headache. Two weeks into recovery Emmalyn was sitting in a chair and said that she felt sick to her stomach, so she ran into the bathroom, I followed and as she was heaving her head went deeper into the toilet. I picked her up and her eyes darted to the right and she couldn’t talk to me. I immediately called 911. When the paramedics arrived, they swept her from my arms and rushed her to the ambulance. They kept her in front of our house in the ambulance for about ten minutes before they came and told me she was having a seizure; they didn’t want to jostle her head, so they called the helicopter. We were told to meet the helicopter at the hospital, which is forty-five minutes away. My husband and I jumped in our van and I don’t think I have ever seen my husband drive so fast; we beat the helicopter there. When the helicopter landed, we were in the ER to greet her when she came off the elevator, and when she did, she was covered in blood and screaming. I looked to the helicopter nurse and she said, “Two minutes before landing she came to and she wanted her mom and pulled out her IV.” She had a forty-five-minute seizure. We are in “small-town,” USA, so the ER did a quick MRI, bloodwork, but no EEG and at the time I didn’t know she should have had one. So, they said she was fine and released her from the hospital. Of course, after speaking with her neurosurgeon the next day she had us in the car to make the five-hour drive for her to be admitted. After three days of tests, they concluded that she had chemical meningitis and put her on medication and anti-seizure meds for six months. Let me tell you that was the scariest time of my life, but Emmalyn took it like a champ. In three months, we had repeat scans, her decompression site looked good, but her syringes didn’t change in size, so we chose to wait and see.

Colton had just finished his Chiari Decompression. He was headache free and doing great! His neurosurgeon came to me and said, “This is a genetic disorder and Emmalyn should be checked.” Two weeks later I took Emmalyn into the Chicago area to be sedated for her first MRI of the brain and spine. Three hours later I met Emmalyn in recovery where she came out of anesthesia smiling. Emmalyn was three years old and asymptomatic, not even a headache. Colton’s neurosurgeon called me the next day and let me know that she was only 5mm herniated, but in the spinal MRI, she had two separate syrinxes. A smaller one in her cervical spine and a very large one in her thoracic spine. Her opinion was to decompress Emmalyn right away as she was very concerned about the two syringes and explained, “With the decompression, it should allow the syringes to dissipate.” So, we scheduled her first decompression for two-weeks later, on July 31st, 2012. Emmalyn went through her first decompression like a champ and was released from hospital after three days. This is when Emmalyn’s headaches started. It seemed like once a day she would be getting a headache. Two weeks into recovery Emmalyn was sitting in a chair and said that she felt sick to her stomach, so she ran into the bathroom, I followed and as she was heaving her head went deeper into the toilet. I picked her up and her eyes darted to the right and she couldn’t talk to me. I immediately called 911. When the paramedics arrived, they swept her from my arms and rushed her to the ambulance. They kept her in front of our house in the ambulance for about ten minutes before they came and told me she was having a seizure; they didn’t want to jostle her head, so they called the helicopter. We were told to meet the helicopter at the hospital, which is forty-five minutes away. My husband and I jumped in our van and I don’t think I have ever seen my husband drive so fast; we beat the helicopter there. When the helicopter landed, we were in the ER to greet her when she came off the elevator, and when she did, she was covered in blood and screaming. I looked to the helicopter nurse and she said, “Two minutes before landing she came to and she wanted her mom and pulled out her IV.” She had a forty-five-minute seizure. We are in “small-town,” USA, so the ER did a quick MRI, bloodwork, but no EEG and at the time I didn’t know she should have had one. So, they said she was fine and released her from the hospital. Of course, after speaking with her neurosurgeon the next day she had us in the car to make the five-hour drive for her to be admitted. After three days of tests, they concluded that she had chemical meningitis and put her on medication and anti-seizure meds for six months. Let me tell you that was the scariest time of my life, but Emmalyn took it like a champ. In three months, we had repeat scans, her decompression site looked good, but her syringes didn’t change in size, so we chose to wait and see.

In 2013, Emmalyn developed leg pain and started having incontinence. She potty trained early and never had problems. After going through more imaging and urodynamics they said that she didn’t look like she was tethered but they were sure that she was. They called it Occult Tethered Cord. So, Emmalyn underwent a tethered cord release on September 27, 2013. She only spent one night in the hospital and was up and doing all well, so they let her go home. After the release, her incontinence subsided but the leg pain continued.

Over the next two years, we monitored Emmalyn and her headaches continued. In 2014, we did our next repeat MRI and it showed that Emmalyn’s syrinx in her thoracic spine had gotten a little longer in length. It concerned her then neurosurgeon and she made the decision that we should do another decompression in hopes to reduce the size of Emmalyn’s syrinx. On July 1st, 2014 Emmalyn went for her second decompression. Once again, she came through everything like a champ. One thing about Emmalyn she is a fighter!

For the next year Emmalyn struggled with more headaches and leg pain, so more imaging was done. She had developed scar tissue that was blocking her CSF flow once again. After the imaging, the decision was made that in November, she would undergo yet another decompression  to clean up the scar tissue so that flow could be reestablished. Emmalyn underwent her third decompression on November 2nd, 2015. She sailed through surgery and the surgeon came out to talk with my dad and me. She explained that Emmalyn’s future could be complicated as she was developing a lot of scar tissue and that would make things more complex because it could continue to block the flow. The pain after these surgeries is something, they don’t prepare you for and after this surgery, it was worse than the last two. She came out swinging and hated everything. They got her pain under control, but it seemed like more pain medication was needed this time to keep it that way. This time, she spent four days in the hospital before returning home.

to clean up the scar tissue so that flow could be reestablished. Emmalyn underwent her third decompression on November 2nd, 2015. She sailed through surgery and the surgeon came out to talk with my dad and me. She explained that Emmalyn’s future could be complicated as she was developing a lot of scar tissue and that would make things more complex because it could continue to block the flow. The pain after these surgeries is something, they don’t prepare you for and after this surgery, it was worse than the last two. She came out swinging and hated everything. They got her pain under control, but it seemed like more pain medication was needed this time to keep it that way. This time, she spent four days in the hospital before returning home.

After the surgery, her pain got a little better. Then on December 29th, our world got turned upside down. We were at my niece’s house in Wisconsin and my mom had run her hand down the back of Emmalyn’s head and she yelled for me to come over there. Emmalyn had a large lump on the back of her head that was squishy. We rushed to the ER in Madison and they took her straight to MRI and that is when we found out Emmalyn had developed her first pseudomeningocele. It was very large. They only let us leave with her when I promised to get an appointment with her neurosurgeon within the next week. On a good note, Emmalyn won her first American Girl Doll Grace while in the ER. She was so excited. It brought a smile to her face in between the bad headaches she was having. At this point in life, Emmalyn had lived with two years of headaches and had become known as the girl with a smile. She always smiled through her pain.

On January 5th, 2016 we took the five-hour drive back to her neurosurgeon. She took one look at the back of her head, and the imaging and she said we would be going back into surgery the next day to repair. Emmalyn was an add-on to their schedule, so she wouldn’t be going to surgery until noon. Keeping a five-year-old with no food or drink after midnight to noon is quite a task, but when the prior surgeries took longer than they thought, going until 5 pm was more than a task. She was mad, tired, hungry and beyond over it. They came to get her and even with all she had been through, she smiled and said, “love you all, see you when I wake up.” She was always so easy going into the operating room. After three hours, her neurosurgeon came out and said there was a pin-sized-hole in the dura. She showed me a picture, and she repaired it with a patch. Once again in true Emmalyn fashion, she woke up swinging, mad and in pain. By this point, they had her pain regimen down to a T, which is SO important. Her recovery went well, and she was out in three days and sent home.

Once again, her headaches and leg pain continued, but she was able to be upright again. In the middle of February, the back of her head became squishy again and her headaches started to get worse when upright. I called her neurosurgeon, and as always, more imaging was ordered, and as I suspected, her pseudomeningocele was back again. She delayed surgery as she wanted to do some research. So, Emmalyn laid down for most of a month. On March 31, we returned to the hospital for her sixth surgery. She went in and did the repair and placed an EVD drain, to check the pressure and drain CSF fluid. The drain was placed for a week, and it was the happiest and pain-free I had seen Emmalyn in over two years. Her pressures were all above 28, which meant high pressure. She made the decision that a VP shunt needed to be placed. Emmalyn went in for her seventh surgery on April 6th. Her Neurosurgeon came out and talked to me and my parents, she let me know that if this patch was to blow and another pseudomeningocele was to appear that at this point she wouldn’t know what to do next, that Emmalyn was too complex for her. I wanted to cry in fear for the first time. My dad said then what, whatever it was we would make it happen. Thank God for my dad, my rock. She said that she would refer us to a specialist she knew of in NYC. I prayed right there this night for god to take care of my little girl and heal her. After she woke up, the pain wasn’t as bad. Shunt placement seemed to be much easier than decompression. She stayed for two more days and was released to return home.

Once again, her headaches and leg pain continued, but she was able to be upright again. In the middle of February, the back of her head became squishy again and her headaches started to get worse when upright. I called her neurosurgeon, and as always, more imaging was ordered, and as I suspected, her pseudomeningocele was back again. She delayed surgery as she wanted to do some research. So, Emmalyn laid down for most of a month. On March 31, we returned to the hospital for her sixth surgery. She went in and did the repair and placed an EVD drain, to check the pressure and drain CSF fluid. The drain was placed for a week, and it was the happiest and pain-free I had seen Emmalyn in over two years. Her pressures were all above 28, which meant high pressure. She made the decision that a VP shunt needed to be placed. Emmalyn went in for her seventh surgery on April 6th. Her Neurosurgeon came out and talked to me and my parents, she let me know that if this patch was to blow and another pseudomeningocele was to appear that at this point she wouldn’t know what to do next, that Emmalyn was too complex for her. I wanted to cry in fear for the first time. My dad said then what, whatever it was we would make it happen. Thank God for my dad, my rock. She said that she would refer us to a specialist she knew of in NYC. I prayed right there this night for god to take care of my little girl and heal her. After she woke up, the pain wasn’t as bad. Shunt placement seemed to be much easier than decompression. She stayed for two more days and was released to return home.

Emmalyn’s headaches continued, and one month later her pseudomeningocele reared its ugly head. I called her neurosurgeon and she did imaging and this leak was bigger than the other two. It consumed the whole back of her head. She made the referral to the specialist in New York City, NY.

After sending all her imaging, op notes, doctor’s notes, and everything else. We consulted with the specialist’s office. An appointment was made to go to NYC and see him on June 10th, 2016. My sister, Emmalyn and I boarded the plane for our first trip ever to NYC. We met with the specialist, who went over all of Emmalyn’s imaging, talked with all of us, and checked Emmalyn over. He let us know that Emmalyn was a very complex case, that her first neurosurgeon had removed too much bone and most likely cause her to have Craniocervical Instability (CCI). He also said that he suspected that she had a connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), and that was why healing had been hard and why the dural patch was not holding. His surgical plan was to go in and once again patch the leak in the dura, clean up the scar tissue, place a titanium plate to hold where her brain was slumping, place an EVD drain again for a week to make sure the VP shunt was needed, and because of the EDS aspect to be closed by a plastic surgeon with muscle flaps to make sure it would hold. Before he would schedule surgery, he wanted to speak with her former neurosurgeon in depth to know what he was in for when he cut open the back of her head. He said that we could fly home and he would be in touch on when surgery would be scheduled.

Emmalyn struggled for a whole summer with severe headaches as we waited for surgery to be scheduled. Finally, at the beginning of September, we received the call that we would be returning to NYC on Sept 15, 2016, for pre-op and surgery on the 19th. Dreams come true and prayers answered. We would have to be in the city for two weeks, as she would be in the hospital for a little over one week. We returned to NYC and everything went as planned. She and I walked to the OR. She had a smile on her face, and she said, “I love you, mommy,” as she went under. As always Emmalyn woke up swinging and in so much pain. We were at a new hospital with nurses and staff that didn’t know her pain regimen, so momma bear kicked into action. At first, they wouldn’t listen when I told them that the only thing that worked for her for the first twenty-four hours after surgery was morphine, and then she could be switched to Oxycodone. Once I was finally heard Emmalyn’s pain was taken care of. Within forty-eight hours Emmalyn was up and walking with her drain and feeling great. Her pressures were still above 28 the whole week so the decision was made to put the VP shunt back in place with the valve set at 1.5. She returned to the OR on September 26th for the shunt and was discharged from the hospital the next day. The next sixty-eight days were the best days of my daughter’s life; she was finally pain-free!

On the 4th of December 2016, Emmalyn’s leg pain returned, and two days later her headaches returned when upright. I emailed her new neurosurgeon immediately. He ordered stat MRIs of the brain and complete spine. I received a copy of the MRIs on disc and looked at them when I got home, and my worst fears came true – the pseudomeningocele had returned. I emailed her neurosurgeon a few images and he called me right away. He explained that he believed the leak was back and he wanted us on a plane ASAP. We flew back to NYC in two days and my parents followed three days later. When we arrived, he admitted her immediately through the ER. He explained surgery would take place on December 14, 2016, for another pseudomeningocele repair. On the 13th of December, he came into her room and switched gears, he believed that her shunt was malfunctioning and there was not a leak. I told him that her symptoms were the same as every leak before and he said he was very sure it wasn’t; so, on the 14th they would do the surgery to check her shunt. He took her into surgery on the 14th and come out and said that there was nothing wrong with the shunt, but he dialed it to 0.5 to help with the CSF and we could return home after post-op.

We returned home in time for Christmas and Emmalyn’s headaches continued to be horrible. I kept in constant contact with her new neurosurgeon about it and he kept saying let’s wait and see. We ended up having some insurance troubles as his office no longer excepted our insurance, so we had to take out an additional private policy for Emmalyn to be able to continue to see him. After all that was solved, we returned to NYC at the beginning of March for an ICP bolt test. Emmalyn returned to the OR on March 2nd, 2017 to have an ICP bolt placed to once again check her pressures as he believed her current VP shunt wasn’t aggressive enough. Her pressures were still a little high but not like before. She was in the hospital for forty-eight hours with the bolt and then it was removed at her bedside. She screamed through the removal. He sat down with us at post-op and talked to us in-depth that he still believed that there was not a leak and that he wanted to place a new VP shunt, with no valve, but instead she would have an anti-siphoning device behind her ear to slow it down when she was upright. He believed this was the best course of action for Emmalyn. He is the specialist, so of course, why would I question it. So, we scheduled her next surgery for March 22nd.

We returned to NYC at the end of the month and she went back into her first surgery of two on March 22, 2017. In the first surgery, he placed an EVD drain to drain CSF and to check pressures again. Her pressures were normal but on the higher size so he proceeded to surgery number two on March 29th. He removed the EVD drain and placed the new no valve shunt and the anti-siphoning device that could be changed when needed. It was a very painful surgery for Emmalyn as the placement of the anti-siphoning device was behind her ear in a very tender spot, and he also let me know she was the first child he had ever placed this in. She had recovered and returned home. Her headaches continued.

We returned to NYC at the end of the month and she went back into her first surgery of two on March 22, 2017. In the first surgery, he placed an EVD drain to drain CSF and to check pressures again. Her pressures were normal but on the higher size so he proceeded to surgery number two on March 29th. He removed the EVD drain and placed the new no valve shunt and the anti-siphoning device that could be changed when needed. It was a very painful surgery for Emmalyn as the placement of the anti-siphoning device was behind her ear in a very tender spot, and he also let me know she was the first child he had ever placed this in. She had recovered and returned home. Her headaches continued.

We had to come back in May for imaging as no one in our area would do MRI’s on her now due to liability issues with the shunt. The pseudomeningocele was still present and her headaches were still strong. He made the decision to give it until July and if things hadn’t improved, he would open the back of her head and check for the leak.

We returned in July and nothing had improved. We sat down to discuss the next surgery and he switched gears again. He said after a discussion with his colleagues, he still didn’t think there was a leak. He then let me know he thought adding a lumbar shunt would help the situation to take care of the pain and the pseudomeningocele. Once again over my better judgment, he is the specialist, so we scheduled surgery, and her lumbar shunt was placed and set at 1.5. It was an easier surgery for her, so her hospital stay wasn’t as long. The next few days at the hotel were horrible her head pain was so she couldn’t even walk or be upright in bed without a debilitating headache. After speaking with her neurosurgeon, he said take her to the ER and have it dialed up to 2.0. Upon arrival at the ER, they checked her shunt and after her previous MRI, the resident dialed it to 0.5 rather than 1.5 (so it was virtually wide open). The current resident dialed it to 2.0 in front of me. Things improved. Recovery from this developed a whole new symptom – stomach pain. Now she had daily headaches, leg pain, and stomach pain, but through it all remained smiling as much as she could. He wanted her back in a month, for new imaging, to see how things were doing.

In a month nothing improved, she just continued to get worse. So, in August we returned for imaging and an appointment. The imaging showed that the pseudomeningocele had almost gone away. He was so happy. I was too, but her symptoms had not gone away at all and now the added stomach pain was causing even more suffering. So, he said we should return again the next month, and they would externalize the shunts to see if the stomach pain would go away and if it did, we would convert the VP to a VA to get the tubing out of her stomach.

We returned in September. He externalized her VP shunt but not the LP. Her stomach pain didn’t improve so he said it wasn’t the shunts, so he took her back into the OR to place her shunts back in place. Although I explained her headache pain was not better and I still believed she had a leak from her dura. He said he was positive there wasn’t a leak.

We returned to Illinois. Her symptoms continued to be debilitating. I emailed him at least five times a week for answers and he quit answering. So, I called his office and they would set up phone call appointments that he never kept. All attempts to contact him were ignored for three long months, while our eight-year-old Emmalyn suffered. Until the day I emailed his college about the problems she was having, asking, begging for anyone to give us a second opinion, and what do you know he called me ten minutes later. He promised he would come up with a plan, and said he thought she needed pain management as everything surgical was stable. After a week of hearing nothing, I emailed him one last time. Asking him to open the back of her head and check for a leak, if there wasn’t one, I would concede to pain management. His office called the next day to set up surgery.

We returned to Illinois. Her symptoms continued to be debilitating. I emailed him at least five times a week for answers and he quit answering. So, I called his office and they would set up phone call appointments that he never kept. All attempts to contact him were ignored for three long months, while our eight-year-old Emmalyn suffered. Until the day I emailed his college about the problems she was having, asking, begging for anyone to give us a second opinion, and what do you know he called me ten minutes later. He promised he would come up with a plan, and said he thought she needed pain management as everything surgical was stable. After a week of hearing nothing, I emailed him one last time. Asking him to open the back of her head and check for a leak, if there wasn’t one, I would concede to pain management. His office called the next day to set up surgery.

We returned to NYC on December 10th for surgery on the 11th. He told me surgery should be less than two hours as he didn’t believe he would find anything. He came out to the waiting room five hours later. He took me outside the waiting room and explain to me that when he opened the back of her head, he found many holes in her dura that were causing a leak. He explained that he went further up on her head and harvested her own tissue and sealed the dura again. He told me that he believed this would secure the dura and we would never have a leak again. He said that the plastic surgeon was closing her up, and I should see her in about an hour. He assured us that he would be up the next day to talk further. What a punch in the gut. Emmalyn woke from surgery in so much pain, but the wonderful PICU team that knew her so well jumped into action. A lot of these nurses have at this point gone from just nurses to being like family to us. Our stay after this surgery was rough, she was hospitalized for ten days and couldn’t be upright longer than forty-five minutes without morphine. Her leaks were sealed, but with two shunts over-draining, her low-pressure pain was beyond belief. Only morphine by pump or IV were helping her pain, but they wanted her off of the morphine and on oxycodone before they’d release her. Her neurosurgeon was in everyday checking on her. Emmalyn’s only request was to be home for Christmas. We were eventually able to get her switched to Oxy and they said she could fly home on the 21st of December. He didn’t want to remove the shunts just yet as he wanted to keep all CSF off the back of her head so the patch would seal. We would return at the end of January to address the shunt issue.

Emmalyn came home for Christmas and spent it lying down, as the pain was at its worst when she was upright. She spent the next month that way until we returned at the end of January to return for surgery to have the lumbar shunt removed on January 31st, 2018. After it was removed her pain was still bad when upright, so her surgeon decided to go back into surgery to externalize her VP shunt and clamp it off to see if things improved, and they did somewhat. So, the decision was made to take her back into the OR again to remove her VP shunt. After three surgeries in ten days, Emmalyn came out with no shunts at all!

We returned home and as always headaches and leg pain had continued. We returned to NYC for post-op and imaging at the beginning of March. All imaging was done, and no leaks were found in the back of the head, but they noticed a “kink” in her brainstem and that her two syrinxes continued to be large. Her neurosurgeon believed everything was stable in her brain, even though the thoughts of CCI were still there. He began to focus on her spine. He sent her for a prone MRI (where she was laying on her stomach), and her surgeon said that she did not look tethered, and we were put back in the “wait and see” category.

We returned home and as always headaches and leg pain had continued. We returned to NYC for post-op and imaging at the beginning of March. All imaging was done, and no leaks were found in the back of the head, but they noticed a “kink” in her brainstem and that her two syrinxes continued to be large. Her neurosurgeon believed everything was stable in her brain, even though the thoughts of CCI were still there. He began to focus on her spine. He sent her for a prone MRI (where she was laying on her stomach), and her surgeon said that she did not look tethered, and we were put back in the “wait and see” category.

Due to insurance reasons, we were unable to see our neurosurgeon for a while, so we were sent back to our original neurosurgeon. After consulting with her she sent us to a new neurosurgeon in her office that specialized in CCI. After doing a flexion MRI, CT, and additional testing the decision was made that Emmalyn needed fusion. She went in on June 20, 2018, for fusion surgery from 0 to C4. Recovery was very rough and wearing the collar wasn’t much better. After her fusion surgery, her headaches seemed to get better, but her leg pain was at an all-time high.

Our insurance issues were resolved and our neurosurgeon that did her fusion thought it best that we return to our neurosurgeon in NYC because he knew her case best. So, we returned in September for more imaging and the next steps. In the process, Emmalyn’s scar on her side where her lumbar shunt was placed was very painful and very large. We consulted with our plastic surgeon and he decided that the scar needed to be revised along with the one on the back of her head, revision surgery was decided to be done on October 2. After our neurosurgeon in NYC reviewed her brain and spine imaging, her thoracic syrinx was still very large, he came up with the plan to go in and check for a tethered cord. He really believed she was not tethered, and he stated if she wasn’t then they would consider shunting her syrinx at a later date. On October 2nd Emmalyn was taken back into surgery for scar revision and exploration of tethered cord. After being in the OR for forty-five minutes our neurosurgeon came out into the waiting room to talk to me. After shaving the back of her head for the scar revision they saw that the screws from her fusion were ready to come through the back of her head. He said he brought his fusion surgeon in and he decided they would probably have to remove the top part of her fusion. I agreed to do what needed to be done to fix the situation. After four hours of surgery, he came out and explained that the side scar had been revised, and after exploring for a tethered cord, he considered her “a complex tethered cord,” and he untethered everything. He then explained that they were keeping her intubated overnight so they could do a CT to make sure she was fully fused before removing the top part of her fusion. Seeing her intubated was one of the hardest things in my life. She woke up once and was so scared and tried to talk. We explained what was happening and she went back to sleep. They did the CT overnight and made the decision she was fused and removed her top fusion the next morning. She came out with no collar and was told she did not have to wear one. We were sent home two weeks later.

The weekend after we returned home Emmalyn started complaining of a bad headache and stated that she heard a cracking noise in her head, and her head felt wobbly. I immediately emailed the two neurosurgeons. The plan was to get a CT on Monday. We found out the donor bone in her fusion had broken. The plan was to put her back in the cervical collar for it to heal. In just a few days of being in the cervical collar, the headaches were horrible, and her incision opened and looked infected. After talking with the neurosurgeons and talking with Emmalyn it was decided to return to NYC to have the top part of her fusion back in. On November 5th she went back in the OR once again to have the top part of the fusion put back in place. It was then that we learned just how extensive the infection had been, and our nightmare battling it began. After fusion surgery, she was placed back in the collar and the plastic surgeon that closed her stated that part of her incision had a blackness to it and needed to be revised and would have to be back in the OR in two weeks for revision. After the revision the infection returned. They put her on antibiotics and sent us home right before Christmas, after eight weeks in the city. Emmalyn’s headaches continued and did not get better, but the incision started to look better. Her round of antibiotics ended, and her incision opened again, so I sent pictures to her plastic surgeon and he wanted us back to NYC as soon as possible. We returned on January 2nd, 2019. We saw plastic surgery, infectious disease, and neurosurgery. Infectious disease was concerned that her hardware was infected, but neurosurgery said it wasn’t. After three weeks in the city, it was decided to take her into the OR and take the infected part off and see how deep it went. It was determined to be superficial, but they decided to keep her on the antibiotics. Her headaches continued to be bad, so the decision was made to keep her in NYC for the next month to monitor her. Her incision healed well on the antibiotics, so they discontinued the antibiotics. On February 27th she was taken into the OR for another ICP bolt, to check to see if high pressure returned. When upright her pressures were at 0 to -5 and laying down, they went as high as 8. Our neurosurgeon let us know that her pressures were normal, and a shunt would not help. After the surgery was done and we were discharged her incision opened, yet again. We went for her post-op visit with the neurosurgeon and he took one look and said her hardware had to be infected and needed to be removed. After speaking with her fusion surgeon, he stated there was no way we should be removing the hardware so soon, as she was not fused. So, they decided to take her in the OR and do a complete washout and cultures and put her on antibiotics indefinitely until the hardware could be removed. On March 11th she was taken into the OR once again and had a complete wash out with antibiotics. After the cultures returned with no answers, her infectious disease doctor put her on Cefadroxil 500mg twice daily until the hardware could be safely removed. After three months in the city, we finally returned home.

The weekend after we returned home Emmalyn started complaining of a bad headache and stated that she heard a cracking noise in her head, and her head felt wobbly. I immediately emailed the two neurosurgeons. The plan was to get a CT on Monday. We found out the donor bone in her fusion had broken. The plan was to put her back in the cervical collar for it to heal. In just a few days of being in the cervical collar, the headaches were horrible, and her incision opened and looked infected. After talking with the neurosurgeons and talking with Emmalyn it was decided to return to NYC to have the top part of her fusion back in. On November 5th she went back in the OR once again to have the top part of the fusion put back in place. It was then that we learned just how extensive the infection had been, and our nightmare battling it began. After fusion surgery, she was placed back in the collar and the plastic surgeon that closed her stated that part of her incision had a blackness to it and needed to be revised and would have to be back in the OR in two weeks for revision. After the revision the infection returned. They put her on antibiotics and sent us home right before Christmas, after eight weeks in the city. Emmalyn’s headaches continued and did not get better, but the incision started to look better. Her round of antibiotics ended, and her incision opened again, so I sent pictures to her plastic surgeon and he wanted us back to NYC as soon as possible. We returned on January 2nd, 2019. We saw plastic surgery, infectious disease, and neurosurgery. Infectious disease was concerned that her hardware was infected, but neurosurgery said it wasn’t. After three weeks in the city, it was decided to take her into the OR and take the infected part off and see how deep it went. It was determined to be superficial, but they decided to keep her on the antibiotics. Her headaches continued to be bad, so the decision was made to keep her in NYC for the next month to monitor her. Her incision healed well on the antibiotics, so they discontinued the antibiotics. On February 27th she was taken into the OR for another ICP bolt, to check to see if high pressure returned. When upright her pressures were at 0 to -5 and laying down, they went as high as 8. Our neurosurgeon let us know that her pressures were normal, and a shunt would not help. After the surgery was done and we were discharged her incision opened, yet again. We went for her post-op visit with the neurosurgeon and he took one look and said her hardware had to be infected and needed to be removed. After speaking with her fusion surgeon, he stated there was no way we should be removing the hardware so soon, as she was not fused. So, they decided to take her in the OR and do a complete washout and cultures and put her on antibiotics indefinitely until the hardware could be removed. On March 11th she was taken into the OR once again and had a complete wash out with antibiotics. After the cultures returned with no answers, her infectious disease doctor put her on Cefadroxil 500mg twice daily until the hardware could be safely removed. After three months in the city, we finally returned home.

Emmalyn’s headaches continued as always. It had been her way of life for seven years. Now the new symptom of nausea started and never left. We returned in May to have her hardware removed. After it was removed her upright headaches came back strong, but her incision healed perfectly. We were there for another six weeks after surgery to be monitored and because of the low-pressure headaches that I knew all too well. I asked our neurosurgeon for a CT myelogram and he refused, saying he “still believed she had instability issues and there was definitely not a leak.” After going back and forth with him for a long time he refused to listen. I decided it was time for a second opinion. I reached out to another specialist and he had many questions and agreed to see her. I let her neurosurgeon know that because all he was willing to do is have her see pain management, we were headed for a second opinion. We left NYC and didn’t look back.

Emmalyn’s headaches continued as always. It had been her way of life for seven years. Now the new symptom of nausea started and never left. We returned in May to have her hardware removed. After it was removed her upright headaches came back strong, but her incision healed perfectly. We were there for another six weeks after surgery to be monitored and because of the low-pressure headaches that I knew all too well. I asked our neurosurgeon for a CT myelogram and he refused, saying he “still believed she had instability issues and there was definitely not a leak.” After going back and forth with him for a long time he refused to listen. I decided it was time for a second opinion. I reached out to another specialist and he had many questions and agreed to see her. I let her neurosurgeon know that because all he was willing to do is have her see pain management, we were headed for a second opinion. We left NYC and didn’t look back.

Her new neurosurgeon in California was very thorough in her initial appointment and understood how much she had been through and he wasn’t going to do any intervention unless it was needed. He did a flexion MRI that showed she was fused, so instability was not the problem. He started by putting her on a medication to raise the pressures in her head, which helped some, but the headaches were still bad when upright or active. We returned home while he pulled a team together for further testing. We returned to  California in September, where we met with a pain team and physical therapy. It was decided she needed a CT Myelogram as they were convinced there was a leak somewhere. After the Myelogram, we met with her neurosurgeon and it was determined Emmalyn had a leak at L1 in her lumbar spine. He recommended an epidural blood patch to repair the leak. We received a call from the pain team that the leak specialist agreed. We returned to sunny California on October 8, 2019, for her blood patch on October 9, 2019. On October 9th Emmalyn went into the OR for her blood patch. She had two blood patches placed due to the presence of scar tissue at her L1 and L2 from her tethered cord surgery. They placed one there but also did a second patch coming up from her tailbone to make sure that it would seal. She struggled for a few days in the hospital with rebound high-pressure, so her neurosurgeon put her on Diamox until we could figure out her new normal.

California in September, where we met with a pain team and physical therapy. It was decided she needed a CT Myelogram as they were convinced there was a leak somewhere. After the Myelogram, we met with her neurosurgeon and it was determined Emmalyn had a leak at L1 in her lumbar spine. He recommended an epidural blood patch to repair the leak. We received a call from the pain team that the leak specialist agreed. We returned to sunny California on October 8, 2019, for her blood patch on October 9, 2019. On October 9th Emmalyn went into the OR for her blood patch. She had two blood patches placed due to the presence of scar tissue at her L1 and L2 from her tethered cord surgery. They placed one there but also did a second patch coming up from her tailbone to make sure that it would seal. She struggled for a few days in the hospital with rebound high-pressure, so her neurosurgeon put her on Diamox until we could figure out her new normal.

After Emmalyn’s lumbar blood patch on October 9th, she had five days with no pain, and the low-pressure headaches (headaches when upright) returned. (Epidural Blood Patches are much less invasive than a surgical dural repair, but they often take multiple attempts to try and seal the leak.) We went home and Emmalyn continued to suffer until we returned on November 20th for a second lumbar blood patch. Her second blood patching offered no relief at all. After being in California for a week we were sent home again to see if it got better over time. They didn’t and Emmalyn started to get discouraged (which is unlike her). After talking with the doctors, the decision was made to return to California on December 10th for a third lumbar blood patch. The third patch offered her one day of relief before her horrible headaches returned. It seems like after every blood patch the headaches would come back worse. After the third blood patch failed the leak specialist decided it was time to try fibrin glue patch as the blood wasn’t sealing. We returned to California on January 14th (causing us to miss her brother’s 13th birthday, which was a hard one for us both, but he understood the urgency to get his sister better). On January 15th Emmalyn was admitted for her fibrin glue patch in the lumbar spine. Unfortunately, it didn’t help, and her headaches came back right away. Feeling pretty defeated the doctors decided to try a patch in her cervical spine as she is known for leaks in that area. We returned home for a month and returned to California on February 4th for a cervical blood patch. She was admitted on February 5th for the patch and the next day was her 11th birthday. She developed a high fever and cough. It was a scary time as they didn’t know what was happening. They ended up admitting her to the hospital and started running tests. The fever kept coming back and it ended up after three days in the hospital she was found to have bronchitis. The fever went away and on the third day she was able to get up and her headache was gone. She was discharged and after two days her headache returned. The bad part about all these blood patches is afterward the patient must lay flat for seventy-two hours as to not blow the patch. It is a difficult process but when it works it is amazing and it’s disheartening hoping for relief each time, only to see her still in pain.

After the fifth patch, the doctors had serious discussions about what was next. Emmalyn’s headaches when upright were worse than they have ever been. After a lot of discussions, it was decided for Emmalyn to return to California on April 1st for another CT Myelogram (to check for remaining spinal leaks) with a Lumbar Puncture (to check her opening pressures), and surgical repair if necessary. The onslaught of COVID-19 hit. With so much unknown, we decided it would be safer to drive to California, rather than flying. Emmalyn and I rented a vehicle and hit the road on March 26th. We didn’t stop much and tried to do two states a day. The ride was a hard one on Emmalyn and the headaches were horrible, but we arrived in California on March 28th. Her Lumbar Puncture revealed that her opening pressure was twenty-four, which is a little on the high side, and not low like they expected. To make it even more confusing, the CT myelogram revealed a small leak still in the lumbar spine. The decision was made to do an EVD drain to drain CSF and recheck her pressures, to address the high-pressure issue first. On April 1st she was admitted for an EVD drain placement for seventy-two hours. She was put in the PICU (Pediatrics Intensive Care Unit) and at first, things weren’t improving at all. They dialed up the drain and as it was draining her headache began to improve by the last day her headache was at a two-out-of-ten, something we haven’t seen in an awfully long time. It was so great to see a genuine smile on Emmalyn. They removed the drain on Saturday afternoon, and she was discharged to the Ronald McDonald House, where we were staying. By Monday, her upright head pain returned with a vengeance. The decision was made to place a VP (ventriculoperitoneal) shunt with a Certas Programmable (adjustable) Valve.

After the fifth patch, the doctors had serious discussions about what was next. Emmalyn’s headaches when upright were worse than they have ever been. After a lot of discussions, it was decided for Emmalyn to return to California on April 1st for another CT Myelogram (to check for remaining spinal leaks) with a Lumbar Puncture (to check her opening pressures), and surgical repair if necessary. The onslaught of COVID-19 hit. With so much unknown, we decided it would be safer to drive to California, rather than flying. Emmalyn and I rented a vehicle and hit the road on March 26th. We didn’t stop much and tried to do two states a day. The ride was a hard one on Emmalyn and the headaches were horrible, but we arrived in California on March 28th. Her Lumbar Puncture revealed that her opening pressure was twenty-four, which is a little on the high side, and not low like they expected. To make it even more confusing, the CT myelogram revealed a small leak still in the lumbar spine. The decision was made to do an EVD drain to drain CSF and recheck her pressures, to address the high-pressure issue first. On April 1st she was admitted for an EVD drain placement for seventy-two hours. She was put in the PICU (Pediatrics Intensive Care Unit) and at first, things weren’t improving at all. They dialed up the drain and as it was draining her headache began to improve by the last day her headache was at a two-out-of-ten, something we haven’t seen in an awfully long time. It was so great to see a genuine smile on Emmalyn. They removed the drain on Saturday afternoon, and she was discharged to the Ronald McDonald House, where we were staying. By Monday, her upright head pain returned with a vengeance. The decision was made to place a VP (ventriculoperitoneal) shunt with a Certas Programmable (adjustable) Valve.

Surgery on April 8th went as planned and Emmalyn’s headaches were all over the place. She ended up being admitted to the hospital for eight days. After a few adjustments, they set her valve to a six and discharged her back to the Ronald McDonald House. Unfortunately, Emmalyn’s upright headaches were still horrible. It was time to bring the leak specialist back into the picture. After many conversations, it was decided to do a Cisternogram, a CT test with nuclear medicine to find a leak. They had to prepare for the test so it couldn’t be done until May 5th. This time, we stayed in California, where she’d be close enough for valve adjustments as needed, and due to the pandemic, we didn’t know what travel restrictions would be implemented. Two more weeks of bad headaches.

Emmalyn went in for her Cisternogram with a Lumbar Puncture to check her opening pressure (which was normal… so the high-pressure was no longer a factor due to the shunt). The Cisternogram is generally a forty-eight-hour series of tests – beginning with an initial CT, another three hours later, another after six hours, then twenty-four-hours, and finally one at forty-eight-hours to check everywhere for a leak. Emmalyn did great and after the twenty-four-hour test, they said they didn’t need to do the next one. After a round-table discussion of doctors regarding the results of the test, it showed that Emmalyn had a leak at L4-5, and this time, they wanted to surgically repair it. On May 13th we went in for Emmalyn’s 38th surgery. Due to her constant leg pain, they also decided to do an ultrasound of her spine while in there to check her Tethered Cord area. She went in for surgery and four-and-a-half hours later the surgeon was out to speak with me. He found the leak and was able to repair it and upon the ultrasound of the spine, found that her spinal cord was complexly tethered again, stating “it was in a ball and he had to untether it.” He let me know that her EDS is severe and that her scar tissue is massive, so he went back in to try and repair all that he could.

Emmalyn went in for her Cisternogram with a Lumbar Puncture to check her opening pressure (which was normal… so the high-pressure was no longer a factor due to the shunt). The Cisternogram is generally a forty-eight-hour series of tests – beginning with an initial CT, another three hours later, another after six hours, then twenty-four-hours, and finally one at forty-eight-hours to check everywhere for a leak. Emmalyn did great and after the twenty-four-hour test, they said they didn’t need to do the next one. After a round-table discussion of doctors regarding the results of the test, it showed that Emmalyn had a leak at L4-5, and this time, they wanted to surgically repair it. On May 13th we went in for Emmalyn’s 38th surgery. Due to her constant leg pain, they also decided to do an ultrasound of her spine while in there to check her Tethered Cord area. She went in for surgery and four-and-a-half hours later the surgeon was out to speak with me. He found the leak and was able to repair it and upon the ultrasound of the spine, found that her spinal cord was complexly tethered again, stating “it was in a ball and he had to untether it.” He let me know that her EDS is severe and that her scar tissue is massive, so he went back in to try and repair all that he could.

Emmalyn was unable to walk after this surgery. That was something that I, as her mom, wasn’t emotionally prepared for, and she wasn’t either. We were prepared for the pain, as she has been through that many times, but on day three after surgery, it was time for her to get up and walk and couldn’t. With all that Emmalyn has been through, never has not been able to walk afterward. This time when her physical therapist got her up to walk, her legs would just give out on her. It was so hard and scary for her and me both. She would cry in frustration and pain, as her headache was still there and remaining at a ten-out-of-ten, around the clock. Her back was hurting worse than her head and now, she couldn’t walk. After a week in the hospital, she was able to walk with a walker, her back pain was still horrible and her headaches still present, so her surgeon decided another MRI was needed. She was taken for her MRI on Wednesday evening, and after a few hours, the neurosurgeon resident came to talk to us. He let us know that either there was a leak or a seroma was present by her lumbar spine and they would have to take her back into surgery the next morning. Emmalyn yelled at  the resident and told him, “No, none of this is making me better it is making me worse.” He was patient and kind and told her if we didn’t do surgery it would continue to get worse yet. With Emmalyn’s blessing, I signed the consent and they took her back into surgery the next morning. After three hours they came out and told me it was a seroma and it was taken care of. By the next day, Emmalyn was ready to get up and her back was feeling somewhat better, but she couldn’t walk again. At this point, we didn’t know how long she would need the walker. We were in the hospital for another five days and over the course, she improved walking with a walker and her back pain subsided, but her headache was back all the time, and laying down wasn’t taking it away. We stayed in California until June 9th, where at this time Emmalyn was back walking on her own, another MRI was performed to check the seroma and it had fully dissipated, but her headaches were still 10/10 and even Dilaudid didn’t help. It was decided it was time to go home and give her a break from surgeries and time to heal, so Emmalyn and I hit the road. We decided to take a long route home to see friends and the Grand Canyon. (Since this has been such a long battle for all of us, I try to find ways to break the monotony of it all whenever I can if she’s up to it.) On day three of the drive (after seeing the Canyon), we stopped to rest and visit a friend, but Emmalyn was in so much pain, she was in tears and said she couldn’t continue with the drive. We had a carload of stuff, so the decision was made to pack everything in boxes and ship them, buy plane tickets out of Denver and fly home. Flights for Emmalyn are horrible, the pressure makes her headaches so much worse.

the resident and told him, “No, none of this is making me better it is making me worse.” He was patient and kind and told her if we didn’t do surgery it would continue to get worse yet. With Emmalyn’s blessing, I signed the consent and they took her back into surgery the next morning. After three hours they came out and told me it was a seroma and it was taken care of. By the next day, Emmalyn was ready to get up and her back was feeling somewhat better, but she couldn’t walk again. At this point, we didn’t know how long she would need the walker. We were in the hospital for another five days and over the course, she improved walking with a walker and her back pain subsided, but her headache was back all the time, and laying down wasn’t taking it away. We stayed in California until June 9th, where at this time Emmalyn was back walking on her own, another MRI was performed to check the seroma and it had fully dissipated, but her headaches were still 10/10 and even Dilaudid didn’t help. It was decided it was time to go home and give her a break from surgeries and time to heal, so Emmalyn and I hit the road. We decided to take a long route home to see friends and the Grand Canyon. (Since this has been such a long battle for all of us, I try to find ways to break the monotony of it all whenever I can if she’s up to it.) On day three of the drive (after seeing the Canyon), we stopped to rest and visit a friend, but Emmalyn was in so much pain, she was in tears and said she couldn’t continue with the drive. We had a carload of stuff, so the decision was made to pack everything in boxes and ship them, buy plane tickets out of Denver and fly home. Flights for Emmalyn are horrible, the pressure makes her headaches so much worse.

We were home for a month with no relief and returned to California on July 6th for a follow-up. It was decided to do a flexion/extension MRI to check her cervical cranial junction and to check where the cerebellum had become adhered to the brain stem. After the MRI, her neurosurgeon called and let me know it was time to surgically go back into the back of her head. He said that her cerebellum was slumping too low into the skull causing traction to the brainstem, also her 4th ventricle was severely dilated, and would likely need to be stented, but it would take a couple of weeks before it could be scheduled. We flew home on July 14th and returned to California on July 27th for what we’re hoping to be her final surgery.

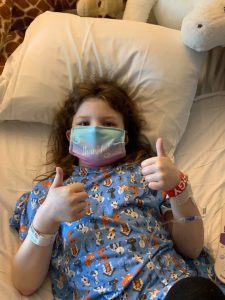

We are now back in California, getting ready for Emmalyn’s fortieth surgery. The surgery is on July 31st, exactly one day after her very first surgery eight years ago. At preop, her surgeon was extremely optimistic that this surgery will help her to feel better and hopefully let her have a more normal life. The surgery is expected to be five-eight hours long as some of this is unknown territory and decisions will have to be made once she’s opened for surgery, as an MRI only tells the surgeon so much. I have every faith in her surgeon that he will do what needs to be done to get Emmalyn better.

The road with EDS, Chiari Malformation, CSF leaks, Tethered Cord Syndrome, Craniocervical Instability, and all the comorbids she’s faced, is such a long road for anyone that has it, but don’t give up, because the right surgeon or doctor will come along and hopefully be able to help make it better! Emmalyn’s story has been long and hard, and more than any little girl should have to endure. It’s impossible to go through forty surgeries in the eight years of her now eleven-year life and have a short story to tell. She’s stronger than any child should have to be and despite all the pain, she tries to maintain a cheerful disposition that brightens everyone’s day. Emmalyn wanted to share her story in hopes that it might help other children in their fight. We hope that her story will help other families understand the importance of advocating for their child, even if it means getting second/third opinions! Don’t believe everything your doctors say, research it for yourselves and push to get the medical care that your child deserves. If a surgeon is willing to do surgery but is unwilling to run tests, walk away, and get another opinion! Ask your child what they’re feeling and when they’re feeling it, as well as any changes that might be helping to relieve the pain (even if the relief is slight) because those are important details; and believe what they tell you even if you’re the only one that believes them. And beyond everything else, don’t give up and don’t give in! Fight it like you’re fighting for your child’s life because that is exactly what you’re doing – that is the fight!

The road with EDS, Chiari Malformation, CSF leaks, Tethered Cord Syndrome, Craniocervical Instability, and all the comorbids she’s faced, is such a long road for anyone that has it, but don’t give up, because the right surgeon or doctor will come along and hopefully be able to help make it better! Emmalyn’s story has been long and hard, and more than any little girl should have to endure. It’s impossible to go through forty surgeries in the eight years of her now eleven-year life and have a short story to tell. She’s stronger than any child should have to be and despite all the pain, she tries to maintain a cheerful disposition that brightens everyone’s day. Emmalyn wanted to share her story in hopes that it might help other children in their fight. We hope that her story will help other families understand the importance of advocating for their child, even if it means getting second/third opinions! Don’t believe everything your doctors say, research it for yourselves and push to get the medical care that your child deserves. If a surgeon is willing to do surgery but is unwilling to run tests, walk away, and get another opinion! Ask your child what they’re feeling and when they’re feeling it, as well as any changes that might be helping to relieve the pain (even if the relief is slight) because those are important details; and believe what they tell you even if you’re the only one that believes them. And beyond everything else, don’t give up and don’t give in! Fight it like you’re fighting for your child’s life because that is exactly what you’re doing – that is the fight!

*Originally published 10/2019, updated -7/2020.

![The Michelle Cole Story – A Chiari Warrior’s Journey [UPDATED]](https://dev.chiaribridges.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/DSC07853t.jpg)

Colton had just finished his Chiari Decompression. He was headache free and doing great! His neurosurgeon came to me and said, “This is a genetic disorder and Emmalyn should be checked.” Two weeks later I took Emmalyn into the Chicago area to be sedated for her first MRI of the brain and spine. Three hours later I met Emmalyn in recovery where she came out of anesthesia smiling. Emmalyn was three years old and asymptomatic, not even a headache. Colton’s neurosurgeon called me the next day and let me know that she was only 5mm herniated, but in the spinal MRI, she had two separate syrinxes. A smaller one in her cervical spine and a very large one in her thoracic spine. Her opinion was to decompress Emmalyn right away as she was very concerned about the two syringes and explained, “With the decompression, it should allow the syringes to dissipate.” So, we scheduled her first decompression for two-weeks later, on July 31st, 2012. Emmalyn went through her first decompression like a champ and was released from hospital after three days. This is when Emmalyn’s headaches started. It seemed like once a day she would be getting a headache. Two weeks into recovery Emmalyn was sitting in a chair and said that she felt sick to her stomach, so she ran into the bathroom, I followed and as she was heaving her head went deeper into the toilet. I picked her up and her eyes darted to the right and she couldn’t talk to me. I immediately called 911. When the paramedics arrived, they swept her from my arms and rushed her to the ambulance. They kept her in front of our house in the ambulance for about ten minutes before they came and told me she was having a seizure; they didn’t want to jostle her head, so they called the helicopter. We were told to meet the helicopter at the hospital, which is forty-five minutes away. My husband and I jumped in our van and I don’t think I have ever seen my husband drive so fast; we beat the helicopter there. When the helicopter landed, we were in the ER to greet her when she came off the elevator, and when she did, she was covered in blood and screaming. I looked to the helicopter nurse and she said, “Two minutes before landing she came to and she wanted her mom and pulled out her IV.” She had a forty-five-minute seizure. We are in “small-town,” USA, so the ER did a quick MRI, bloodwork, but no EEG and at the time I didn’t know she should have had one. So, they said she was fine and released her from the hospital. Of course, after speaking with her neurosurgeon the next day she had us in the car to make the five-hour drive for her to be admitted. After three days of tests, they concluded that she had chemical meningitis and put her on medication and anti-seizure meds for six months. Let me tell you that was the scariest time of my life, but Emmalyn took it like a champ. In three months, we had repeat scans, her decompression site looked good, but her syringes didn’t change in size, so we chose to wait and see.

Colton had just finished his Chiari Decompression. He was headache free and doing great! His neurosurgeon came to me and said, “This is a genetic disorder and Emmalyn should be checked.” Two weeks later I took Emmalyn into the Chicago area to be sedated for her first MRI of the brain and spine. Three hours later I met Emmalyn in recovery where she came out of anesthesia smiling. Emmalyn was three years old and asymptomatic, not even a headache. Colton’s neurosurgeon called me the next day and let me know that she was only 5mm herniated, but in the spinal MRI, she had two separate syrinxes. A smaller one in her cervical spine and a very large one in her thoracic spine. Her opinion was to decompress Emmalyn right away as she was very concerned about the two syringes and explained, “With the decompression, it should allow the syringes to dissipate.” So, we scheduled her first decompression for two-weeks later, on July 31st, 2012. Emmalyn went through her first decompression like a champ and was released from hospital after three days. This is when Emmalyn’s headaches started. It seemed like once a day she would be getting a headache. Two weeks into recovery Emmalyn was sitting in a chair and said that she felt sick to her stomach, so she ran into the bathroom, I followed and as she was heaving her head went deeper into the toilet. I picked her up and her eyes darted to the right and she couldn’t talk to me. I immediately called 911. When the paramedics arrived, they swept her from my arms and rushed her to the ambulance. They kept her in front of our house in the ambulance for about ten minutes before they came and told me she was having a seizure; they didn’t want to jostle her head, so they called the helicopter. We were told to meet the helicopter at the hospital, which is forty-five minutes away. My husband and I jumped in our van and I don’t think I have ever seen my husband drive so fast; we beat the helicopter there. When the helicopter landed, we were in the ER to greet her when she came off the elevator, and when she did, she was covered in blood and screaming. I looked to the helicopter nurse and she said, “Two minutes before landing she came to and she wanted her mom and pulled out her IV.” She had a forty-five-minute seizure. We are in “small-town,” USA, so the ER did a quick MRI, bloodwork, but no EEG and at the time I didn’t know she should have had one. So, they said she was fine and released her from the hospital. Of course, after speaking with her neurosurgeon the next day she had us in the car to make the five-hour drive for her to be admitted. After three days of tests, they concluded that she had chemical meningitis and put her on medication and anti-seizure meds for six months. Let me tell you that was the scariest time of my life, but Emmalyn took it like a champ. In three months, we had repeat scans, her decompression site looked good, but her syringes didn’t change in size, so we chose to wait and see. to clean up the scar tissue so that flow could be reestablished. Emmalyn underwent her third decompression on November 2nd, 2015. She sailed through surgery and the surgeon came out to talk with my dad and me. She explained that Emmalyn’s future could be complicated as she was developing a lot of scar tissue and that would make things more complex because it could continue to block the flow. The pain after these surgeries is something, they don’t prepare you for and after this surgery, it was worse than the last two. She came out swinging and hated everything. They got her pain under control, but it seemed like more pain medication was needed this time to keep it that way. This time, she spent four days in the hospital before returning home.

to clean up the scar tissue so that flow could be reestablished. Emmalyn underwent her third decompression on November 2nd, 2015. She sailed through surgery and the surgeon came out to talk with my dad and me. She explained that Emmalyn’s future could be complicated as she was developing a lot of scar tissue and that would make things more complex because it could continue to block the flow. The pain after these surgeries is something, they don’t prepare you for and after this surgery, it was worse than the last two. She came out swinging and hated everything. They got her pain under control, but it seemed like more pain medication was needed this time to keep it that way. This time, she spent four days in the hospital before returning home. Once again, her headaches and leg pain continued, but she was able to be upright again. In the middle of February, the back of her head became squishy again and her headaches started to get worse when upright. I called her neurosurgeon, and as always, more imaging was ordered, and as I suspected, her pseudomeningocele was back again. She delayed surgery as she wanted to do some research. So, Emmalyn laid down for most of a month. On March 31, we returned to the hospital for her sixth surgery. She went in and did the repair and placed an EVD drain, to check the pressure and drain CSF fluid. The drain was placed for a week, and it was the happiest and pain-free I had seen Emmalyn in over two years. Her pressures were all above 28, which meant high pressure. She made the decision that a VP shunt needed to be placed. Emmalyn went in for her seventh surgery on April 6th. Her Neurosurgeon came out and talked to me and my parents, she let me know that if this patch was to blow and another pseudomeningocele was to appear that at this point she wouldn’t know what to do next, that Emmalyn was too complex for her. I wanted to cry in fear for the first time. My dad said then what, whatever it was we would make it happen. Thank God for my dad, my rock. She said that she would refer us to a specialist she knew of in NYC. I prayed right there this night for god to take care of my little girl and heal her. After she woke up, the pain wasn’t as bad. Shunt placement seemed to be much easier than decompression. She stayed for two more days and was released to return home.

Once again, her headaches and leg pain continued, but she was able to be upright again. In the middle of February, the back of her head became squishy again and her headaches started to get worse when upright. I called her neurosurgeon, and as always, more imaging was ordered, and as I suspected, her pseudomeningocele was back again. She delayed surgery as she wanted to do some research. So, Emmalyn laid down for most of a month. On March 31, we returned to the hospital for her sixth surgery. She went in and did the repair and placed an EVD drain, to check the pressure and drain CSF fluid. The drain was placed for a week, and it was the happiest and pain-free I had seen Emmalyn in over two years. Her pressures were all above 28, which meant high pressure. She made the decision that a VP shunt needed to be placed. Emmalyn went in for her seventh surgery on April 6th. Her Neurosurgeon came out and talked to me and my parents, she let me know that if this patch was to blow and another pseudomeningocele was to appear that at this point she wouldn’t know what to do next, that Emmalyn was too complex for her. I wanted to cry in fear for the first time. My dad said then what, whatever it was we would make it happen. Thank God for my dad, my rock. She said that she would refer us to a specialist she knew of in NYC. I prayed right there this night for god to take care of my little girl and heal her. After she woke up, the pain wasn’t as bad. Shunt placement seemed to be much easier than decompression. She stayed for two more days and was released to return home.

We returned to NYC at the end of the month and she went back into her first surgery of two on March 22, 2017. In the first surgery, he placed an EVD drain to drain CSF and to check pressures again. Her pressures were normal but on the higher size so he proceeded to surgery number two on March 29th. He removed the EVD drain and placed the new no valve shunt and the anti-siphoning device that could be changed when needed. It was a very painful surgery for Emmalyn as the placement of the anti-siphoning device was behind her ear in a very tender spot, and he also let me know she was the first child he had ever placed this in. She had recovered and returned home. Her headaches continued.

We returned to NYC at the end of the month and she went back into her first surgery of two on March 22, 2017. In the first surgery, he placed an EVD drain to drain CSF and to check pressures again. Her pressures were normal but on the higher size so he proceeded to surgery number two on March 29th. He removed the EVD drain and placed the new no valve shunt and the anti-siphoning device that could be changed when needed. It was a very painful surgery for Emmalyn as the placement of the anti-siphoning device was behind her ear in a very tender spot, and he also let me know she was the first child he had ever placed this in. She had recovered and returned home. Her headaches continued. We returned to Illinois. Her symptoms continued to be debilitating. I emailed him at least five times a week for answers and he quit answering. So, I called his office and they would set up phone call appointments that he never kept. All attempts to contact him were ignored for three long months, while our eight-year-old Emmalyn suffered. Until the day I emailed his college about the problems she was having, asking, begging for anyone to give us a second opinion, and what do you know he called me ten minutes later. He promised he would come up with a plan, and said he thought she needed pain management as everything surgical was stable. After a week of hearing nothing, I emailed him one last time. Asking him to open the back of her head and check for a leak, if there wasn’t one, I would concede to pain management. His office called the next day to set up surgery.

We returned to Illinois. Her symptoms continued to be debilitating. I emailed him at least five times a week for answers and he quit answering. So, I called his office and they would set up phone call appointments that he never kept. All attempts to contact him were ignored for three long months, while our eight-year-old Emmalyn suffered. Until the day I emailed his college about the problems she was having, asking, begging for anyone to give us a second opinion, and what do you know he called me ten minutes later. He promised he would come up with a plan, and said he thought she needed pain management as everything surgical was stable. After a week of hearing nothing, I emailed him one last time. Asking him to open the back of her head and check for a leak, if there wasn’t one, I would concede to pain management. His office called the next day to set up surgery. We returned home and as always headaches and leg pain had continued. We returned to NYC for post-op and imaging at the beginning of March. All imaging was done, and no leaks were found in the back of the head, but they noticed a “kink” in her brainstem and that her two syrinxes continued to be large. Her neurosurgeon believed everything was stable in her brain, even though the thoughts of CCI were still there. He began to focus on her spine. He sent her for a prone MRI (where she was laying on her stomach), and her surgeon said that she did not look tethered, and we were put back in the “wait and see” category.

We returned home and as always headaches and leg pain had continued. We returned to NYC for post-op and imaging at the beginning of March. All imaging was done, and no leaks were found in the back of the head, but they noticed a “kink” in her brainstem and that her two syrinxes continued to be large. Her neurosurgeon believed everything was stable in her brain, even though the thoughts of CCI were still there. He began to focus on her spine. He sent her for a prone MRI (where she was laying on her stomach), and her surgeon said that she did not look tethered, and we were put back in the “wait and see” category. The weekend after we returned home Emmalyn started complaining of a bad headache and stated that she heard a cracking noise in her head, and her head felt wobbly. I immediately emailed the two neurosurgeons. The plan was to get a CT on Monday. We found out the donor bone in her fusion had broken. The plan was to put her back in the cervical collar for it to heal. In just a few days of being in the cervical collar, the headaches were horrible, and her incision opened and looked infected. After talking with the neurosurgeons and talking with Emmalyn it was decided to return to NYC to have the top part of her fusion back in. On November 5th she went back in the OR once again to have the top part of the fusion put back in place. It was then that we learned just how extensive the infection had been, and our nightmare battling it began. After fusion surgery, she was placed back in the collar and the plastic surgeon that closed her stated that part of her incision had a blackness to it and needed to be revised and would have to be back in the OR in two weeks for revision. After the revision the infection returned. They put her on antibiotics and sent us home right before Christmas, after eight weeks in the city. Emmalyn’s headaches continued and did not get better, but the incision started to look better. Her round of antibiotics ended, and her incision opened again, so I sent pictures to her plastic surgeon and he wanted us back to NYC as soon as possible. We returned on January 2nd, 2019. We saw plastic surgery, infectious disease, and neurosurgery. Infectious disease was concerned that her hardware was infected, but neurosurgery said it wasn’t. After three weeks in the city, it was decided to take her into the OR and take the infected part off and see how deep it went. It was determined to be superficial, but they decided to keep her on the antibiotics. Her headaches continued to be bad, so the decision was made to keep her in NYC for the next month to monitor her. Her incision healed well on the antibiotics, so they discontinued the antibiotics. On February 27th she was taken into the OR for another ICP bolt, to check to see if high pressure returned. When upright her pressures were at 0 to -5 and laying down, they went as high as 8. Our neurosurgeon let us know that her pressures were normal, and a shunt would not help. After the surgery was done and we were discharged her incision opened, yet again. We went for her post-op visit with the neurosurgeon and he took one look and said her hardware had to be infected and needed to be removed. After speaking with her fusion surgeon, he stated there was no way we should be removing the hardware so soon, as she was not fused. So, they decided to take her in the OR and do a complete washout and cultures and put her on antibiotics indefinitely until the hardware could be removed. On March 11th she was taken into the OR once again and had a complete wash out with antibiotics. After the cultures returned with no answers, her infectious disease doctor put her on Cefadroxil 500mg twice daily until the hardware could be safely removed. After three months in the city, we finally returned home.